1. J Health Care Mark. 1993 Fall;13(3):60-5.

1. J Health Care Mark. 1993 Fall;13(3):60-5.

Patient callback program: a quality improvement, customer service, and marketing tool.

Gombeski WR Jr(1), Miller PJ, Hahn JH, Gillette CM, Belinson JL, Bravo LN, Curry

PS.

Author information:

(1)Cleveland Clinic Foundation, OH.

The authors developed, implemented, and evaluated a callback program in which

hospital patients are contacted three weeks after discharge to resolve clinical

or service concerns. Of the more than 2,000 patients contacted during the

initial pilot test, 6% said they had a clinical concern and were promptly

directed to a physician’s office. A randomized/controlled study comparing a

control group of patients (who were not called) to an experimental group

(called) shows that several satisfaction measures increased positively within

the experimental group. The authors conclude that the Patient Callback Program

contributes to more effective clinical care and to perceptions of higher

customer service.

PMID: 10129817 [Indexed for MEDLINE]

2. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016 Jan;20(1):47-51. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000153.

Intimate Partner Violence and Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening: A Gynecologic Oncology Fellow Research Network Study.

Levinson KL(1), Jernigan AM, Flocke SA, Tergas AI, Gunderson CC, Huh WK,

Wilkinson-Ryan I, Lawson PJ, Fader AN, Belinson JL.

Author information:

(1)1The Kelly Gynecologic Oncology Service, Department of Gynecology and

Obstetrics, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD; 2Divsion of Gynecologic

Oncology, Women’s Health Institute, The Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH;

3Department of Family Medicine and Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Case Western

Reserve University, Cleveland, OH; 4Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology,

Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Columbia University Medical Center, New York,

NY; 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Gynecologic Oncology,

University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, OK; 6Department of Obstetrics and

Gynecology, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, University of Alabama at

Birmingham, Birmingham, AL; 7Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division

of Gynecologic Oncology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO; and 8Preventive

Oncology International, Cleveland, OH.

OBJECTIVES: The aims of the study were to examine barriers to cervical cancer

screening among women who have experienced intimate partner violence (IPV) and

accessed domestic violence shelters, to compare barriers among those up-to-date

(UTD) and not UTD on screening, and to evaluate acceptability of human

papillomavirus self-sampling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS: This is a cross-sectional survey in which domestic

violence shelters in Ohio were identified and women completed an anonymous

survey assessing UTD screening status, barriers related to screening, history of

IPV, intention to follow up on abnormal screening, and acceptability of

self-sampling. Characteristics of UTD and not UTD women were compared using

Mann-Whitney U tests.

RESULTS: A total of 142 women from 11 shelters completed the survey.

Twenty-three percent of women were not UTD. Women who were not UTD reported more

access-related barriers (mean = 2.2 vs 1.8; p = .006). There was no difference

in reported IPV-related barriers between women who were not UTD and those who

are UTD (mean = 2.51 in not UTD vs 2.24 in UTD; p = .13). Regarding future

screening, of the women who expressed a preference, more women not UTD preferred

self-sampling than UTD women (32% vs 14%; p = .05).

CONCLUSIONS: In this study, access-related barriers were more commonly reported

among women not UTD with screening. Addressing these barriers at domestic

violence shelters may improve screening among not UTD women. Self-sampling may

also be one feasible approach to support screening in this population.

DOI: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000153

PMCID: PMC4693628

PMID: 26704329 [Indexed for MEDLINE]

Conflict of interest statement: Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the

authors has any competing financial interests.

3. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2025 Jan 9;34(1):159-165. doi:

10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-24-0999.

A Mail-Based HPV Self-Collection Program to Increase Cervical Cancer Screening in Appalachia: Results of a Group Randomized Trial.

Reiter PL(1)(2), Shoben AB(1)(2), Cooper S(1), Ashcraft AM(3), McKim Mitchell

E(4), Dignan M(5), Cromo M(5), Walunis J(2), Flinner D(2), Boatman D(3)(6),

Hauser L(7), Ruffin MT 4th(8), Belinson JL(9)(10), Anderson RT(11)(12),

Kennedy-Rea S(3)(6), Paskett ED(1)(2)(13), Katz ML(1)(2).

Author information:

(1)College of Public Health, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio.

(2)Comprehensive Cancer Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio.

(3)School of Medicine, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia.

(4)School of Nursing, University of Virgnia, Charlottesville, Virginia.

(5)College of Medicine, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky.

(6)West Virginia University Cancer Institute, Morgantown, West Virginia.

(7)Cancer Center, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia.

(8)Family and Community Medicine, Penn State Health, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

(9)Preventive Oncology International, Inc., Shaker Heights, Ohio.

(10)Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology, Cleveland

Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

(11)Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Virginia,

Charlottesville, Virginia.

(12)School of Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia.

(13)Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, The Ohio State University,

Columbus, Ohio.

BACKGROUND: Despite the promise of mail-based human papillomavirus (HPV)

self-collection programs for increasing cervical cancer screening, few have been

evaluated in the United States. We report the results of a mail-based HPV

self-collection program for underscreened women living in Appalachia.

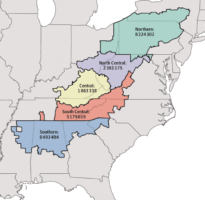

METHODS: We conducted a group randomized trial from 2021 to 2022 in the

Appalachian regions of Kentucky, Ohio, Virginia, and West Virgnia. Participants

were women of ages 30 to 64 years who were underscreened for cervical cancer and

from a participating health system. Participants in the intervention group (n =

464) were mailed an HPV self-collection kit followed by telephone-based patient

navigation (if needed), and participants in the usual care group (n = 338) were

mailed a reminder letter to get a clinic-based cervical cancer screening test.

Generalized linear mixed models compared cervical cancer screening between the

study groups.

RESULTS: Overall, 14.9% of participants in the intervention group and 5.0% of

participants in the usual care group were screened for cervical cancer. The

mail-based HPV self-collection intervention increased cervical cancer screening

compared with the usual care group (OR, 3.30; 95% confidence interval,

1.90-5.72; P = 0.005). One or more high-risk HPV types were detected in 10.5% of

the returned HPV self-collection kits. Among the participants in the

intervention group whom patient navigators attempted to contact, 44.2% were

successfully reached.

CONCLUSIONS: HPV self-collection increased cervical cancer screening, and future

efforts are needed to determine how to optimize such programs, including the

delivery of patient navigation services.

IMPACT: Mail-based HPV self-collection programs are a viable strategy for

increasing cervical cancer screening among underscreened women living in

Appalachia.

©2024 American Association for Cancer Research.

DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-24-0999

PMCID: PMC11717618

PMID: 39445831 [Indexed for MEDLINE]

Conflict of interest statement: Dr. Belinson serves as a Medical Advisor to

Atila Biosystems. Dr. Paskett receives grant funding from Merck Foundation,

Genentech, Guardant Health, Astra Zeneca, and Pfizer for work not related to

this research. She is also an Advisory Board Member for Merck and GSK.